Football season is about to begin. You may recall, when a player’s knee hits the ground and he’s touched by a defender, play is called dead. Often the quarterback “takes a knee” to stop the clock. But this post is not about football! Rather a look at our marvelous and incredible knees, the mid-point of our lower extremities — the runner’s drive train. Since knees are the most common site of running injuries, it’s worth reviewing how they function.

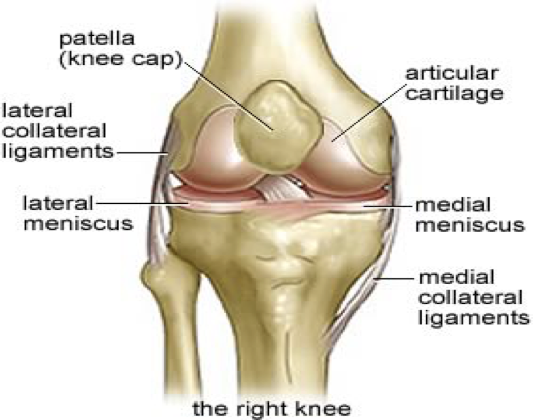

Pictured below, the knee is the largest joint in the body. The knee actually has three joints: the tibiofemoral (largest, lying between our thigh and lower leg and generally thought of as the knee joint), the patellofemoral (kneecap), and the tibiofibular (below the kneecap and not directly part of the knee movement.) I’ll focus first on the tibiofemoral joint here, which functions as a hinge.

Unlike the hip joint, where there is significant bony structure, most of the knee’s stability comes from soft tissue – ligaments, tendons, muscles, cartilage, menisci, bursa, and fat pads. This constitution allows for significant range of motion – for example, we can bend our knee to touch our butt with our foot.

When looking at knee anatomy, physiology, and biomechanics, one quickly realizes how much is going on. Being in the middle of our lower body kinetic chain, if something is not right in the hips or ankle/feet, it usually wreaks havoc in the knee. Amidst all the knee hardware is a lot of viscous synovial fluid, the lubricant that reduces friction. We think ice is slippery. But the inherent friction in a normal knee joint is 20 times less than walking on ice!

First, let’s address a misconception that running is inherently bad for our knees, that we wear down our precious cartilage with each step. It’s not that simple!! In fact, the research shows a runner in good health and lean weight will likely have more cartilage than a person who does not perform weight-bearing exercise. This follows Wolff’s Law, which holds that bone (and other types of connective tissue, such as cartilage) adapt to loads under which they are placed. Further, cartilage has no blood or nutrient supply – this is provided by the synovial fluid that bathes the cartilage within the knee capsule. And that bathing is enhanced by vigorous movement. So weight-bearing exercise stimulates the integrity of cartilage rather than damaging it.

But here’s the rub: the bones and cartilage can’t do it alone. The knee’s stability relies heavily on strong muscles, tendons, and ligaments to ensure undue weight is not placed directly on the articulating surfaces of the knee joint. Running exerts a force roughly three times body weight on the knee, so all of these components need to be doing their job to avoid damage. It’s true undue stress can wear down our cartilage. Also as we age, we experience a slower rate of tissue replacement and repair, decreased water content (healthy cartilage is 80% water!) and have less robust muscles and tendons. We cannot defeat all of these aging processes but the rate of change can be mitigated. Strength training is one way to do that. For example, properly performed squats strengthen all the muscles surrounding the knee. However, one of the last things runners seem to take time for is resistance training.

Virtually all runners have had a bout or two (or more!) with knee pain. In fact, the knee is the most prevalent site of runner injuries, clocking in at about 40% in any particular year. Runners may have acute knee injuries, from a fall, an awkward twist, or from activities other than running. But the most prevalent issue for runners is chronic pain, with patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) at the top of the list.

The patella (our kneecap) is tightly surrounded by muscles, tendons, and ligaments. It covers the patellofemoral joint (PFJ) and serves as a fulcrum when we bend and straighten our knee. The pain, often called “runners knee,” is due to the underside or sides of the patella rubbing against the bone below it. The alignment of the knee and the strength of the muscles surrounding it, in particular the quadriceps, can help keep the kneecap on track and ward off PFPS.

Another debilitating source of knee pain is osteoarthritis, a self-perpetuating condition where depleted cartilage results in bone-on-bone friction. Ideally a strength training program begun early in a runner’s career can help avert this condition. In any event, osteoarthritis is a complicated condition warranting its own blog and that will be forthcoming.

Suffice it to say, knees are vital to lifelong running. And it behooves us to give them their due attention and care!